An Assassinated CEO, The Psychology of Identity, and My Personal Story

Insights Into How Inequality and Weak Competition Policy Fracture Society

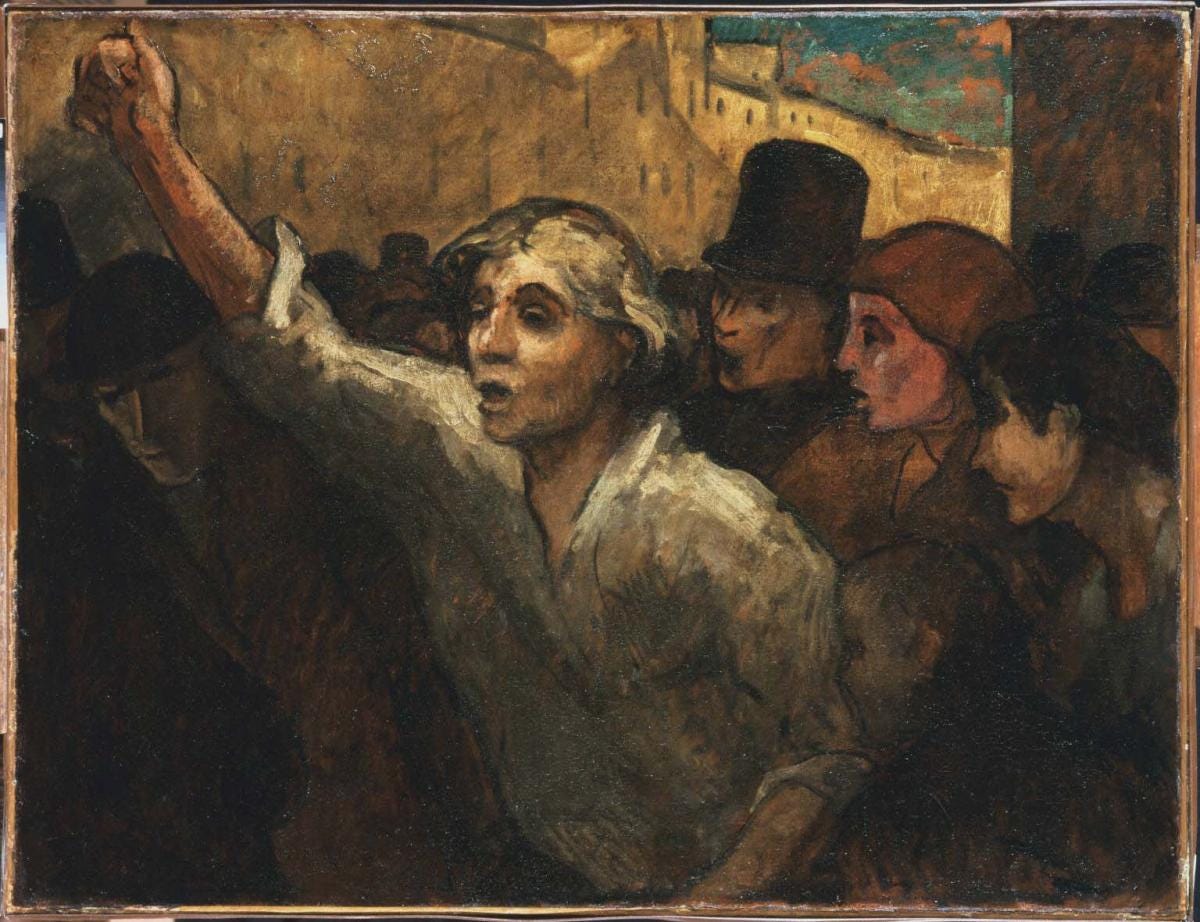

Why have so many people praised the assassin who executed the CEO of UnitedHealthCare? The widespread experience of being denied important, life-altering health services is undeniably a direct factor. But a deeper issue lies in the contempt people feel toward anticompetitive monopolies and oligopolies–giant entities that exploit the public and wield undue influence over our political and economic systems.

In Canada and other Western countries, elites have robbed ordinary people of opportunities for prosperity. Their acquiescent partners in government have dismantled systems that at one time fairly distributed economic liberty. This liberty played a key role in the psychological sensemaking that underpinned decades of stability by providing a possibility of economic prosperity to average workers. This sensemaking fueled ambition, effort, and investment to seize opportunities. The ensuing economic boom created a golden age of prosperity for the baby boomer generation, leading to sprawling neighborhoods for a rapidly growing, upwardly mobile middle class.

However, shifts in policies have allowed unchecked market power to erode the value of labor while transferring wealth and opportunities from workers to executives and shareholders. New generations have been locked out of pathways to prosperity, creating unprecedented inequality and giving rise to a culture of resentment.

Inequality increases susceptibility to misinformation (Salvador Casara et al., 2022) and radicalization (Franc & Pavlović, 2023). There is also a causal link between inequality and political violence (Braithwaite et al., 2016). The Royal Mounted Canadian Police (RCMP) has warned the government that the cost-of-living crisis risks triggering widespread rioting once young people come to terms with the hopelessness of their dire economic prospects (Hopper, 2024; Thompson, 2024). In the inevitable brutal police crackdowns that would follow, protestors would predictably be painted as criminals, rather than acknowledged as desperate, powerless citizens that have no realistic pathways to escape financial ruin and modern serfdom.

Researchers have studied the psychological processes that transform outrage at the perceived unfairness of the status quo into political violence (e.g., Becker & Tausch, 2015; Power, 2018; van den Bos, 2020). These studies show that violent civil unrest emerges after nonviolent anger fails to elicit tangible improvements from elites.

We must prevent this catastrophe before rising inequality ignites the kind of deprivation-fueled political violence that has plagued so many societies for generations.

The first step in tackling these challenges is understanding how long-term consequences of regulatory policies interact with psychological processes to produce conditions that promote stability vs. social unrest. I’ve spent significant chunks of my career in various spaces including psychology, antitrust consulting, and collective action litigations. Lately, I find myself wearing more than one hat at a time and thinking about how we’ve ended up in this mess.

This thinking has also led me to reflect on my journey in life. I’ve been extremely lucky and fortunate in many respects. But I was dealt a shit hand. Not as bad as some but easily worse than most in a developed Western country. I could have succumbed to thinking and ideation that in the aggregate produces social unrest–that would have been my path of least resistance. What saved me was the perception of a possibility to escape the socioeconomic status I inherited from my parents, and valuing that possibility instead of developing a psychological self concept radicalized by forces indifferent to suffering and misery. Understanding the nature of this perception is the key in driving motivation to improve outcomes for individuals and society.

I’m going to share my thoughts, starting with insights from my personal history. In future articles, I’ll write about how competition policy and market structure ultimately impact perception and behavior, focusing on implications for the stability of societies.

Socioeconomic inheritance

I was born in Montreal and am a first generation Canadian. My earliest memories date back to when I was 2 and half years old. Three years old is a more typical early boundary. In my case, the years lost to childhood amnesia ended upon the arrival of my first sibling, which is known to trigger the beginning of episodic memory and the formation of an earlier life history (Usher & Neisser, 1993).

My parents were quintessential immigrants: Poor, uneducated, and unskilled. When my father first arrived, I think he took whatever odd jobs he could find. In the 1980s, he worked as a welder for a few years until globalization devastated Canada’s industrial-sector (Gagnon, 2017). After that, he returned to taking any low-skill job he could get until he retired. He was never a people person. To say he was unpleasant would be putting it mildly. I don’t recall him ever having a friend. He frequently got into arguments at work, occasionally escalating to physical altercations. He also had a habit of rage-quitting jobs. His relationships with my mother, siblings, and me have always been fractious.

My mother worked in the textile sector, which declined in Montreal around the same time as the welding job market. However, she managed to stay employed in the shrinking local textile industry and, after switching companies a couple of times, worked for the same employer for nearly 30 years until she retired. It was unskilled labor and physically demanding – the work mostly consisted of standing all day in front of machines, manually feeding in rolls of fabric, anticipating errors and adjusting the machines accordingly before they ruined a batch of fabric. My mother developed knee problems early on, which became a chronic issue she still struggles with today.

During my earliest recalled years, I think my family vacillated a few times between the poor end of middle class and just plain poor. We probably spent more time being the latter. There was little consumerism in our household. From a young age, I was aware that we faced serious financial challenges. We moved a lot. When I was 3 or 4 years old, my parents had somehow saved enough for a downpayment but bought more house than they should have – they had to sell it by the time I was 5, I believe at a loss, when interest rates skyrocketed during the 1980s. My parents rented afterwards for many years.

My dad always drove cars that seemed to be on the verge of complete failure. In addition to constantly needing repairs, they often didn’t have heating during Montreal’s cold winters and stalled at the worst possible moments. I remember one car in particular that would stall and need a “push start” seemingly on every trip. When the car stalled, my dad got out of the car, braced his left hand on the door frame and his right hand on the steering wheel, pushed the car until it reached a speed I can no longer remember, and then jumped into the driver’s seat of the rolling car and popped the clutch to force the engine to turn over (i.e., start the car).

Once I was approximately 6 or 7 years old, I would help push from the rear while my mother and sister sat nervously in the car. I can no longer remember whether my dad expected me to push or I insisted on helping, as kids that age often do. I can’t imagine my assistance was at all helpful. It’s possible my dad was using me as a prop to motivate bystanders to help, which they occasionally did. In any case, particularly stressful were times helping my dad push start the car at intersections covered in slush. Not infrequently, I slipped and fell forward, broke the fall using my hands, and the dirty slush soaked through my mittens. Once we got the car running, I would try to wipe my freezing hands as best as I could on the upholstery of the car seat until they felt dry enough to sit on so I could warm them up.

I was also a latchkey kid: Starting in grade 1, I would arrive at an empty apartment, unlock the door with a key strung around my neck, park myself in front of the TV, and wait for my parents to arrive so that we could eat supper together. During that first winter of arriving at an empty home, when the days became shorter, I panicked the first few times my parents arrived long after dark. To cope with the sudden uncontrollable anxiety, I went outside, stood in the middle of the street, and hoped to catch a glimpse of their car from a distance to reassure myself that they had not died in a car accident. On one such evening, I accidentally locked myself out and had to buzz a neighbor to let me back into the building. Her apartment was near the entrance and she stepped out to see who it was. I quickly composed myself before she opened the door, apologized for buzzing, and explained that my parents weren’t home to let me in. She looked visibly annoyed. I remember thinking at the time that she was angry because I must have interrupted her supper with her family. But thinking back now, I wonder if she was upset because my parents had left me on my own. Maybe it was both.

To make matters worse, my parents also had a deeply troubled marriage. While many factors influence marital harmony, it would probably surprise no one that the risk of parental discord increases in families facing dire financial straits (Paat, 2011). Still, I think my parents were particularly ill-matched: Troubled seems like an understatement, and understatement feels woefully inadequate to describe the gap. Weekends and holidays were particularly nerve-wracking and violence was the norm. I suspect my father often waited until I was out of sight in another room to unleash the worst of his violence. I can still vividly recall the vicious cocktail of fear, anger, and despair that seized my three-year-old self upon hearing my mother’s panicked cries while she tried to escape my father’s blows, the chaos punctuated by the sounds of objects crashing on the floor.

Despite all this adversity, my parents maintained a mostly–at least outwardly–pleasant demeanor and hopeful attitude. Over time, their financial circumstances improved enough for them to purchase and pay off a modest house. They still live there and their relationship remains deeply dysfunctional.

While my parents never had the means to support my education, even after their financial situation improved, I still managed on my own after a false start.

Anger vs. contempt

While I was aware during my earliest years that I was underprivileged, I obliviously didn’t feel too held back by it because everyone I knew came from a working class family. After graduating high school, I started encountering peers from more varied socioeconomic backgrounds. I then began to more clearly evince the extent of my relative deprivation and the uphill battle I faced. Moving beyond my socioeconomic inheritance began to seem like a mirage I would never reach.

Geography was an obstacle too. The hours-long commute from my parents’ house was interminable – full days of classes and studying preceded by exhausting bus rides at ungodly hours in the freezing cold got the best of me.

I didn’t earn enough from my part-time job to move closer to school or buy a car so I dropped out, abandoning the idea of higher education, and began working full time. My leisure activities shifted from people I grew up with to a jovial, hard-luck, and binge-drinking crowd coalescing around my not-yet-fully-formed adulthood. We partied a lot and the friendships were deeply intense, as is typical during that stage of life.

But looking back now, I realize most of us had been broken by poverty. Many were from families that had been poor for generations in Canada. Institutions and the economy had failed such families. Multigenerational anger had not motivated successive governments to create tangible opportunities to help these families lift themselves out of poverty.

These systemic failures transformed anger over their struggles into contempt for elites. While anger directed at a person or group generally includes a hostile action tendency, its social function is to motivate the target to meet perceived obligations and ultimately facilitate reconciliation (Fischer & Roseman, 2007).

In contrast, contempt arises when the target consistently fails to respond to anger and does not adjust their behavior to meet perceived obligations. Contempt is a reaction to the target’s unresponsiveness – it indicates that the one feeling contempt perceives no way to influence the target and has given up on changing the target’s behavior or reconciling with them (Fischer & Roseman, 2007). Contempt disrupts the relationship by motivating physical exclusion and distancing of the target from social, emotional, and economic aspects of life.

Anger and contempt directed toward the government or corporations serve similar functions (Tausch et al., 2011). Angry citizens voice their dissatisfaction through criticism and lawful protests, hoping elites will fulfill their responsibilities. In contrast, citizens who feel contempt resort to disruptive non-cooperation and political violence, having abandoned hope of reconciliation with elites perceived as unable or unwilling to meet their obligations.

Many years after my misspent youth with my hard-luck friends, I developed a scientific, research-based understanding of the differential development of anger and contempt as a part of my graduate studies in experimental psychology. But even at that tender age all those years ago, I could see the clearcut, intuitive relationship between inequality and contempt for authorities: Economic deprivation had fueled views that inherently rejected the moral authority and legal order of a government perceived to be inept, unsympathetic, and/or corrupt. We were all very young but by the time I left the group after alienating my friends by seeking to get more out of life, several of them had gotten into serious legal trouble.

By that time, boredom and slightly better finances motivated me to go back to school. I then worked in software engineering for a few years. I got bored again and went back to school a second time – I went all the way and completed a PhD in Psychology. Afterwards, I worked at the intersection of data science and antitrust law to support collective action litigations.

I think a key driver in my parents’ and my own trajectory was the perception that we had a shot at upward mobility. We weren’t naive and recognized that there was corruption and structures that favored elites. But unlike the friends of my young adulthood, my parents and I had not been radicalized by marginalization. We had not given up on the system, which allowed us to perceive and value a possibility to improve outcomes within it. The perception of a shot at economic mobility justified investment in oneself and in Canadian society.

In retrospect, the undue influence of big money interests on political and economic systems had already reduced social mobility to a compelling fiction to coerce the masses. By the time I was a young adult searching for my place in the world, upward mobility had become slim to none for many, entirely non-existent for most, and any evidence to the contrary–including my own success–was a reflection of overly optimistic beliefs that overlooked failures while focusing solely on successes (i.e., survivorship bias).

But I bought into the fiction. The narrative drove masses of people like my parents and me to work tirelessly toward an improbable shot at economic security. This drive kept everyone focused on climbing the economic ladder instead of scrutinizing structural inequalities.

Undue market power, upward mobility, and radicalization

Now, after generations of social stability, this fiction has been shattered. Unchecked concentrations of market power exploited by giant firms have gradually eroded the value of labor to the point of obliterating even the fiction of upward mobility. The door to prosperity, which had been barely ajar, has now been slammed completely shut by the influence of these giant firms on economic, political, and social systems, locking out anyone born into families lacking the wealth threshold to access economic security. The impact of these firms on society has dramatically augmented the salience of structural inequalities, giving rise to the culture of resentment, division, and hostility that we grapple with today.

As a young adult waking up from a funk, I didn’t understand why my motivation to seek more out of life didn’t resonate with the people around me, but I eventually learned about the psychological processes at work. People that have similar socioeconomic circumstances and who hold a common understanding of their social position form an in-group. When a more powerful out-group (e.g., government) has a different understanding of the people within the in-group and treats them accordingly, the unexpected circumstances forced upon the in-group triggers changes in their self-concept. If people expect to be treated fairly, violating that expectation radicalizes their self-concept, promoting a redefinition of their cause and a willingness to abandon the rules in their conflict with the out-group (Drury & Reicher, 2000).

The friends of my youth generally didn’t share my desire to succeed within the system because expectations of fair treatment, violated across generations, had radicalized their self-concepts, producing a disdain for authorities and a willingness to operate outside the legal order. I think I never succumbed to the same radical perspectives because I never expected to be treated fairly. The childhood trauma my parents inflicted on me may have, in a twist of irony, inoculated me from group dynamics that change self concepts through violated expectations of fair treatment. Obviously, this is not some kind of recommendation – my childhood likely produced many negative outcomes. Moreover, even if it did somehow spare me, as I am theorizing, from the radicalizing impact of systemic unfairness, it’s likely an anomalous effect that we could not reasonably expect to reproduce.

In contrast, the impact of systemic unfairness on the average citizen is highly predictable. Perceived unfairness has a well-documented relationship with both legal forms of collective actions and violent social unrest (Becker & Tausch, 2015; Power, 2018; van den Bos, 2020). The culture of resentment, the cost-of-living crisis, and the erosion of wages have increased susceptibility to misinformation and set the stage for widespread radicalization.

People’s violated expectations of fair treatment by elites have fueled a surge in extremism. Unprecedented inequality has unleashed volcanic forces beneath society’s fragile surface, threatening to erupt in violent social unrest. Corporations and elites have exploited workers, unchecked, for so long and to such an extreme degree that the masses, consumed by contempt, are now cheering the execution of a CEO.

Is the cheering the mark of social decay, or does the true rot lie in the socially sanctioned murders committed by health insurance companies? Or perhaps the core of this decay is embedded in decades of deregulated policies that have enriched the ruling class at the expense of the livelihoods—and lives—of ordinary citizens.

In any case, we must confront the reality that big money interests and their well-paid consultants will continue to lie, cheat, and steal, while their complicit partners in government let society and ecosystems crumble. Elites won’t save us—we must cultivate a shared sense of purpose to inspire decisive action in defense of our democracy, liberty, and natural wealth.

To chart a path forward, we must first understand how we arrived here. There’s growing recognition that policy shifts beginning in the 1970s and 80s gradually dismantled pathways to prosperity for workers while enabling staggering financial gains and the consolidation of political power among elites. These changes facilitated the rise of corporate giants that undermine democracy to entrench their market dominance, stifle competition for labor, and drive soaring inequality.

Giant firms have also played a central role in eroding the psychological sensemaking that motivates individuals to strive for a better life, which has underpinned decades of social stability in Western countries. The perceived unfairness of the status quo, coupled with the unresponsiveness of elites to citizens’ anger, lies at the heart of increasingly radical views among ordinary people.

In my next article, I will examine the policy changes that have enabled the concentration of vast economic and political power to accumulate in the hands of a few, creating existential threats to society. In subsequent articles, I will explore the psychological processes, triggered by perceived unfairness, that drive radicalization and political violence–forces that, if left unchecked, could unravel the fabric of society.

References

Becker, J. C., & Tausch, N. (2015). A dynamic model of engagement in normative and non-normative collective action: Psychological antecedents, consequences, and barriers. European Review of Social Psychology, 26(1), 43–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2015.1094265

Braithwaite, A., Dasandi, N., & Hudson, D. (2016). Does poverty cause conflict? Isolating the causal origins of the conflict trap. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 33(1), 45-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894214559673

Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2000). Collective action and psychological change: The emergence of new social identities. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39(Pt 4), 579-604. 10.1348/014466600164642

Fischer, A. H., & Roseman, I. J. (2007). Beat them or ban them: The characteristics and social functions of anger and contempt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 103-115. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.103

Franc, R., & Pavlović, T. (2023). Inequality and Radicalisation: Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Terrorism and Political Violence, 35(4), 85-810. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1974845

Gagnon, J. (2017, March 14). Industrialization in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 18, 2024, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/industrialization

Hopper, T. (2024, March 20). Secret RCMP report warns Canadians may revolt once they realize how broke they are. National Post. https://nationalpost.com/opinion/secret-rcmp-report-warns-canadians-may-revolt-once-they-realize-how-broke-they-are

Paat, Y.-F. (2011). The Link Between Financial Strain, Interparental Discord and Children’s Antisocial Behaviors. Journal of Family Violence, 26, 195-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-010-9354-0

Power, S. A. (2018). The Deprivation-Protest Paradox: How the Perception of Unfair Economic Inequality Leads to Civic Unrest. Current Anthropology, 59(6), 765-789. 0.1086/700679

Salvador Casara, B. G., Suitner, C., & Jetten, J. (2022). The impact of economic inequality on conspiracy beliefs. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 98, Article 104245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104245

Tausch, N., Becker, J. C., Spears, R., Christ, O., Saab, R., Singh, P., & Siddiqui, R. (2011). Explaining radical group behavior: Developing emotion and efficacy routes to normative and nonnormative collective action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 129-148. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

Thompson, E. (2024, March 10). Canada faces a series of 'crises' that will test it in the coming years, RCMP warns. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/rcmp-police-future-trends-1.7138046

Usher, J. A., & Neisser, U. (1993). Childhood amnesia and the beginnings of memory for four early life events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 122(2), 155-165. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0096-3445.122.2.155

van den Bos, K. (2020). Unfairness and Radicalization. Annual Review of Psychology, 71, 563–588. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050953

Bravo! That was an excellent analysis of modern events. It highlights a key failing of modern democracy in countries like Canada and the United States. Some comments:

> In Canada and other Western countries, elites have robbed ordinary people of opportunities for prosperity. Their acquiescent partners in government have dismantled systems that at one time fairly distributed economic liberty.

One of the biggest challenges in fact is that society will need an entirely new definition of prosperity because traditional prosperity is unsustainable. So we are faced with two problems: giving people upward mobility but first finding a space that creates the possibility of that mobility.

> These studies show that violent civil unrest emerges after nonviolent anger fails to elicit tangible improvements from elites.

I think it's possible that there are no (serious) tangible improvements from the elites. In a way, the power structure has sort of painted itself in a corner. It has created wealth but the entire underlying mechanism of that wealth creation is based on the industry of exploitation, making themselves much more efficient and people much less so. While traditionally, this efficiency has trickled down just enough to give the impression of improvement, I think the elites have hit a wall: their entire system can longer go forward without showing obvious cracks.

So I think we can expect more civil unrest.

> We must prevent this catastrophe before rising inequality ignites the kind of deprivation-fueled political violence that has plagued so many societies for generations.

I wonder if maybe the goal is not to completely avoid "deprivation-fueld political violence" but to channel it so that it burns in a controlled fashion, and is actually effective. After all, not all political violence leads to an untenable situation of chaos. It is entirely possible that the right sort of movement would actually lead much more quickly to a fairer society than waiting for the megacorporations to hand us a few scraps. Because if you look at it, political violence, while overtly disturbing, is far less disturbing than the systemic violence of the current system.

> The perceived unfairness of the status quo, coupled with the unresponsiveness of elites to citizens’ anger, lies at the heart of increasingly radical views among ordinary people.

I would phrase that a little differently, and say that the system of the elites itself is becoming increasingly more radical in what it is attempting to accomplish, and the views of the ordinary only seem radical in contrast to the radical nature of the elites. If you violently run into someone on the street and push them to the ground, it may seem radical, but that act becomes seen as entirely normal and compassionate if we also add the fact that you have pushed that person out of the way of an oncoming truck.